What is “Venetian Plaster?”

When someone asks me what I do, or what I’m putting on a wall I am designing, the inevitable answer is tricky. I typically say, “Venetian Plaster,” however that isn’t necessarily always true. Let me explain.

What we refer to as “Venetian Plaster” is really a subcategory of a much larger category of products and techniques. There is an overarching commonality in Venetian Plaster, Tadelakt, and surfacing products like Concrete Plaster. That commonality is they are all lime-based. All of these products employ the use of hydrated lime as their main component. This is something we have been developing and working with for thousands and thousands and thousands of years - probably tens of thousands of years. You can read more about that here and here.

In reality, they are all essentially made of the same components - just in different ratios and minor tweaks.

Tadelakt refers to the use of this lime plaster, using limestone with particular mineral compositions and specialized techniques (originally developed in Morocco around 2000 years ago), to provide a hydrophobic surface suitable in wet-use areas. This lime plaster was applied using a specialized technique which became known as Tadelakt. Roman baths and fountains - some still in use today - were created using this plaster and technique.

Concrete plaster is also lime-based, however with a higher ratio of Portland cement added to allow for coatings of concrete that can be worked into all kinds of textures, effects, and styles - from polished, to pitted, to textures imitating wood framework and other industrial touches. They can even be treated with products to create actual rust and water stains to accentuate industrial styles.

But what about “Venetian Plaster?”

During the Renaissance in Venice, Italy, a building boom was underway. There was a huge problem though. The city of Venice had been built on wet, marshy land. This was on purpose, as it provided a more defensible position from Germanic and Hun invaders which was a real problem during the city’s establishing years.

There was a huge tradeoff due to this decision, however. Their homes and buildings could not be built with, nor contain, anything of significant weight. Buildings created out of solid marble had literally sunk into the mud. Some innovation was needed.

Using the vast supply of marble scraps available, an architect named Andrea Palladio began experimenting by grinding up these scraps into what they called “marble flour” and adding it to lime putty (the result of heating limestone to high temperatures and then slaking the byproduct with water, at which point it stabilizes into a smooth paste, you can read more about that here).

The result was the ability to create the depth and movement of marble stone as the overlapping layers of the plaster were carefully applied and worked to the desired result. These thin layers of marbleized plaster allowed for the look and feel of marble, without the weight.

The name they gave this plaster was actually “Marmorino” which translates from Italian into “little marble,” however in the 20th century products in Italy bearing the name Veneziano (Venetian) became available and popular, leading to the American-coined label of “Venetian Plaster” as these Italian products hit the US in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

In fact, if you go searching for plaster products online or at a local dealer using the term Venetian Plaster, you will likely find lines of products that have “Marmorino” in the name and/or description.

While people usually imagine the traditional style or look, it can bring out almost anything you're envisioning. A stunning and varied array of looks, styles, colors and finishes can be achieved using this versatile material.

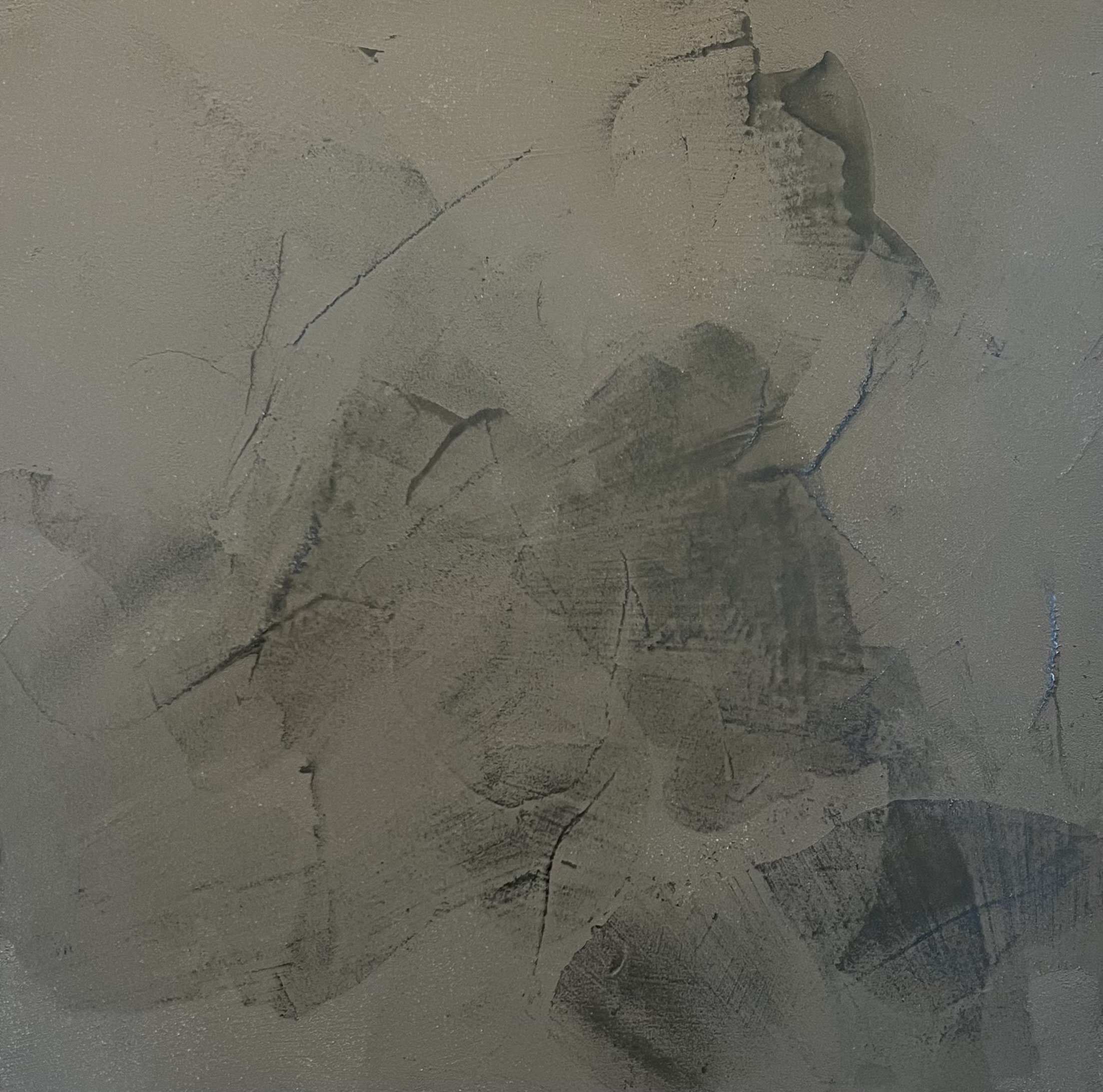

Marmorino (Venetian Plaster) Wall - in the hands of a professional, the result is the subtle illusion of texture and movement, however, if you ran your hand along it, it feels like perfectly flat and smooth stone

Marmoino + Texture + Gold Leafing creates this incredible, custom style, demonstrating the versatility and endless possibilities of lime plaster

Using mineral tints, lime plaster can be any imaginable color, including matching any major paint brand color

Black Marmorino creating interesting texture over a layer of metallic gold Marmorino that shimmers through the voids

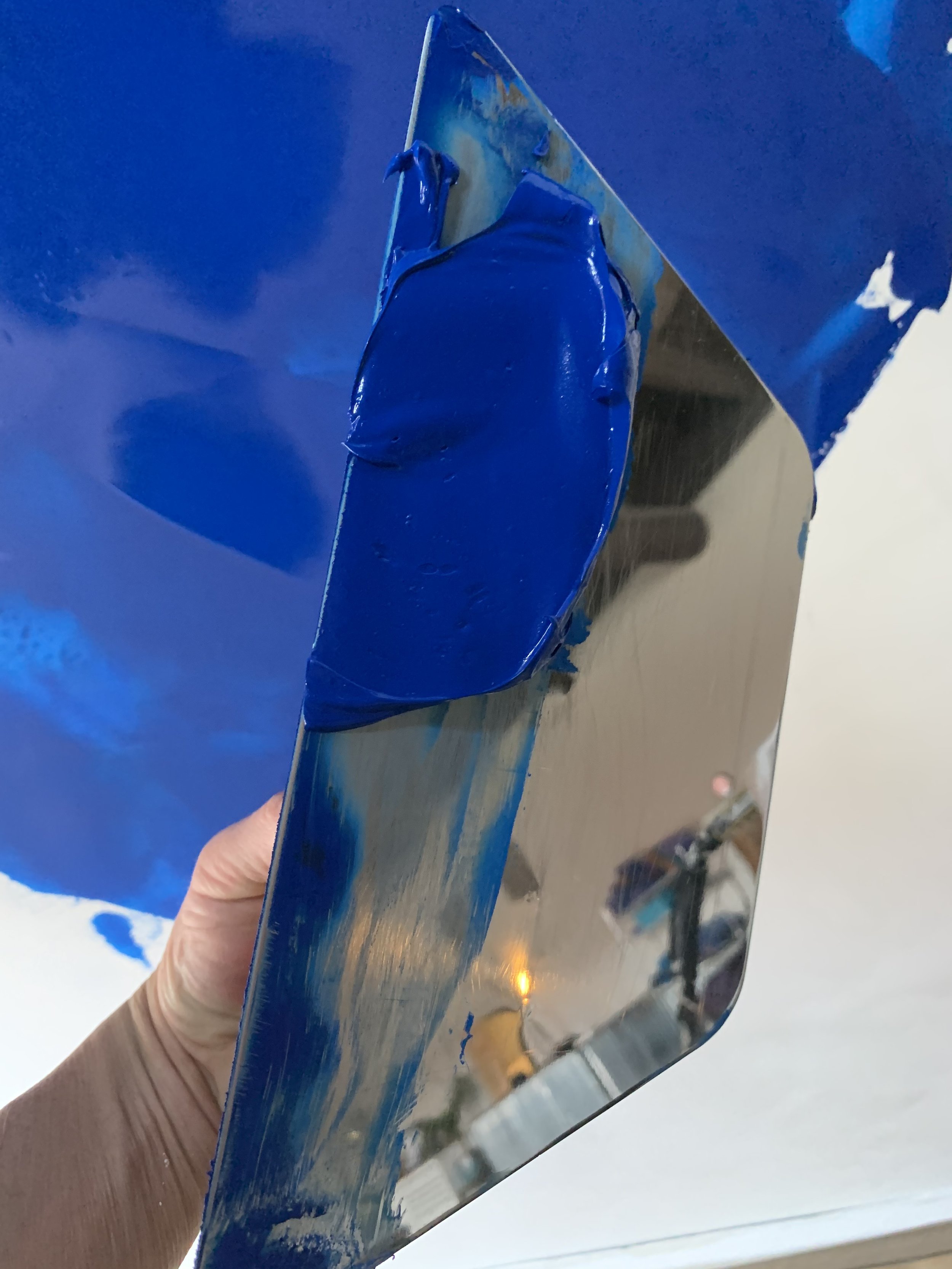

You will likely also come across product lines that use the term “Grasello” in the name or description, though they may also use more branded names like “mirror”, “gloss”, “silk” etc. Italian for “lump of fat,” it became the term used to refer to Venetian Plaster that includes marble particles that are incredible small in diameter (we are talking microns here) which produces a super smooth plaster with no grit or aggregate. The result is the ability to achieve a shiny, perfectly smooth, mirror like finish that mimics the look of polished marble. While technically still Marmorino, this material is typically referred to as Grasello, while the former is most often referring to lime plasters with larger aggregate sizes. The grain size of the mineral additives plays a role in how much texture and sheen can be obtained. Some knowledge is required to select the right plaster for the desired result.

Venetian Plaster with very small grains of ground marble added, known as “Grasello” in Italy, can be worked to a perfectly smooth, mirror-like shine. It is a fantastic choice for offices, restaurants, hotels, bars, spas, salons, and other spaces that convey luxury and a feeling of sleek, stylish cleanliness

This is the same wall from a different angle - perfectly smooth, polished to a mirror shine, with all this interesting movement and the illusion of texture - when many people hear the term “Venetian Plaster” they often think of this specific look and finish - however it is just one of infinite possibilities

Grasello in Grapevine Green brings an elegant, sophisticated feel to this private wine cellar.

Like many monikers, the name “Venetian Plaster” became an umbrella term for a variety of distinct materials. However, in reality, everything from Grasello, to Marmorino (aka, Venetian Plaster), to Tadelakt, to Concrete Plasters, all really fall under the umbrella of lime-based plasters. Tweaks in their ratios of minerals and the amount and size of any added aggregates create a vast array of finishes, styles, uses, and specialized products - however, the various components that make up these plasters are essentially the same. Think Coke and Pepsi - same ingredients just put together using a different recipe.

Ancient Solutions for a Modern World

The benefits of this amazing material have been with it for millennia, characteristics that turn out to be exactly what we are looking for in our modern times with modern problems.

Lime plasters are made of mineral components making them natural, with no VOCs, no chemicals, no toxins. It is literally made from rocks. It is even tinted using minerals. Being rock, it is fireproof, reducing the amount of fuel avaialble during such events and containing nothing flammable or volatile. No dangerous fumes or gases either.

Due to its high lime content, the surfaces cure to a pH of around 13. This is the same alkalinity as bleach and presents an anti-fungal, anti-mold, anti-microbial surface in a world where that is all of a sudden a serious priority.

While the production of these materials does release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere (though measures are taken to capture it during production in many countries), the curing process begins a period of what is called carbonatation, as the plaster begins to take in CO₂ from the air around it, capturing the Carbon atoms while releasing the Oxygen atoms back into the atmosphere through the evaporation of moisture. During this process, the plaster quite literally turns back into solid rock. These surfaces breathe, and in the process pull more carbon out of the air than is emitted during its production.

These environmental and health advanatages are why lime plaster is a major focus of green building initiatives working to create safer, healthier, more sustainable spaces to work and live in.

A Stunning Marmorino (Venetian Plaster) Bathroom

The walls feel like smooth stone with a matte to satin level of sheen. These walls were sealed with a natural wax-based product that will protect its beauty and surface from water and people running their hands along them - which they make you want to do ;)