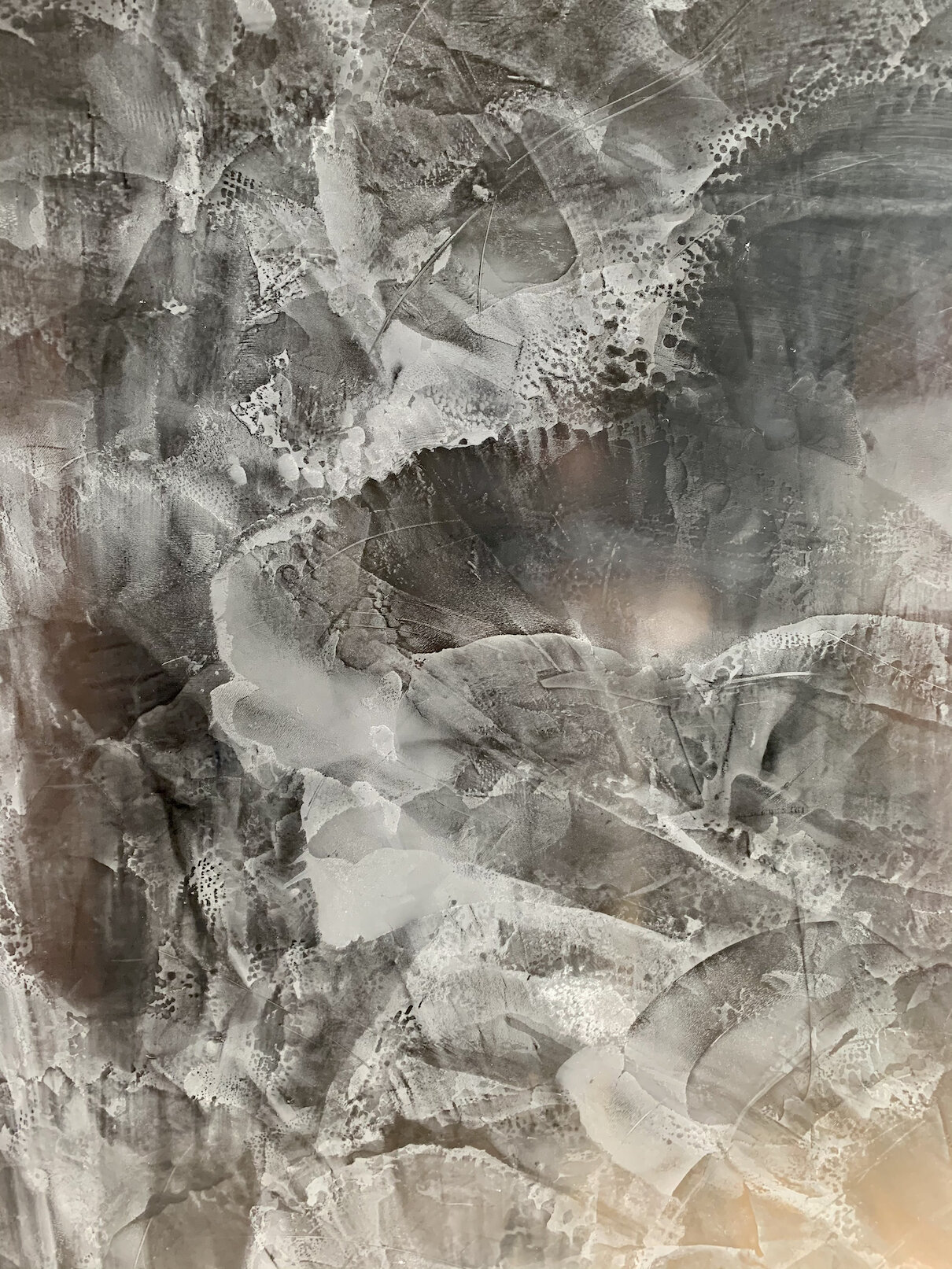

Venetian Plaster

Ancient. Yet, Perfect for The Modern World.

Ancient.

Based upon archaeological discoveries and research, the use of lime-based plasters goes back at least 12,000 years. Evidence of the use of this building material is seen throughout our ancient past in sites like Gobekli Tepe, Catalhyouk, and then throughout Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Minoan, Greek, Chinese, North African, and other civilizations all over the world. From our earliest primitive structures, to the opulent buildings and interiors of the Renaissance, lime plaster is a thread running continuously through it all.

Lime Plasters were used throughout the Great Pyramids and other incredible building projects of Ancient Egypt

So, how did they even figure this whole thing out?

That’s a question we may never fully be able to answer, but we can make some informed guesses based on the process - one that has not significantly changed for thousands of years.

What we refer to as “Venetian Plaster” - now a blanket term for a variety of natural lime plasters, named for a resurgence of the material during the Renaissance period in Venice - starts out as limestone.

Rock. That’s it.

What our ancient ancestors discovered - probably though a little bit of accident, followed by experimentation - was that if they burned these rocks at very high heat in ovens or kilns, they eventually reduced into a powder. Thanks to our modern scientific understanding, we know what chemical processes are at work.

Limestone’s chemical name is Calcium Carbonate. Probably sounds familiar - especially if you’ve ever read a package of Tums or Rolaids. Literally the same substance. If you are old enough to remember chalk being used on school blackboards, that chalk was also calcium carbonate (today it is mostly made of Gypsum, just in case you’re into fun facts).

When heated to high temperature (approaching 1500℉), it loses Carbon Dioxide (CO₂), leaving behind a byproduct known as “Quicklime”, and denoted chemically as Calcium Oxide (CaO). This is a very unstable substance, reacting quite violently when exposed to water. Thus, the colloquial name Quicklime - “quick” being used in the old English sense of “alive, or active".”

Calcium Oxide (CaO), known as “quicklime,” the byproduct of burning limestone (Calcium Carbonate, CaCO₃) in a kiln; once slaked with water it will become Calcium Hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂)

Through more accidents, observations and experimentation, our ancestors found out they could stabilize the Quicklime though a process known as “slaking.” Essentially, inundating and combining it with water. The Quick Lime reacts with the water immediately, causing it to heat, reaching temperatures up to 300°F as the water boils. During the slaking, the quicklime picks up hydrogen and oxygen, stabilizing into Calcium Hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂). The end result is what is called “lime putty.” It could be spread and manipulated.

The Toreador Fresco, Crete c. 1550 BCE - Lime Plaster with Natural Pigments

What was amazing about this stuff, was that as it dried, it turned back into rock, becoming incredibly resilient, so much so that many ancient walls, frescoes, floors and ceilings completed using lime plaster still stand today after thousands of years. Turning to our modern understanding, we can know why this is the case. It turns out, while the lime plaster is drying, it begins a curing process. As water is evaporated away, Carbon Dioxide is absorbed. In a very real sense, these walls “breathe” - pulling CO₂ in, trapping the Carbon, and releasing Hydrogen and Oxygen through the evaporation of water molecules. As this process occurs, the Calcium Hydroxide transforms back into its original state, Calcium Carbonate - Limetstone.

Stone Alchemy.

The Alchemical symbol for Quicklime - in alchemy, the transformative process of slaking quicklime led to it being associated with the element of Fire

And we figured it out thousands, even tens of thousands, of years ago.

Since we are humans doing a bunch of human stuff, over time, we innovated and got creative. During the building boom of the Renaissance, in the city of Venice, they were facing a huge problem. The city had been founded about a 1000 years earlier, and was intentionally built upon marshy, wet land to provide a better defense against invasions from Germanic and Hun tribes - the ones who literally took down the Roman Empire. However, in the 1500s as they were exploding in new artistic endeavors and incredible building projects, the solid marble and stone was causing buildings to literally sink.

A solution was needed.

The architect Andrea Palladio is credited with turning to an ancient material - lime plaster - and experimenting (just like his ancient ancestors did). Due to all of this building and artistic development, there was a wealth of scrap marble readily available, and so he began grinding the marble into what is called “marble flour” (think the consistency of cornstarch or powdered sugar, fine, fine dust). By adding this to the lime plaster, he was able to create the look, feel and impact of marble, but in thin layers that didn’t sink the building.

His version of lime plaster (with marble powders mixed in) became known as Marmorino, meaning, “little marble,” and is the most popular plaster used in homes, restaurants, bars, and businesses still to this day. By adjusting the size of the marble granules, it was found that a variety of textures, feels, and looks could be achieved - from mirror shiny and smooth, to silky matte, to tactile and textured.

In the 20th century, as industry, manufacturing and global trade exploded, lime plaster once again had a resurgence in Italy and was marketed as “Stucco Veneziano” which translates to Venetian Plaster in English. Since the 1970s or so, this label has been used for a wide variety of lime-based plaster products (some of which aren’t technically Venetian Plaster, but whatever, that’s what people know it as.)

Today’s natural lime plasters are composed of the same ingredients, and are processed the same way as they have for millennia. Only now, thanks to advancements in mineral aggregates, colorants and other natural additives, the variety, workability, effects, finishes, colors, and textures are virtually unlimited.

Perfect for the Modern World.

Venetian Plaster starts as this. Limestone rocks. Strangely, it ends up as this too, after being manipulated and formed into beautiful surfaces

The raw materials needed are Limestone and Water. Readily available and easily obtained resources that are environmentally sustained within the cycle of the process. The end result is not the destruction of any resource, but rather a transportation of the limestone - through a chemical process - to another location, into another form, resulting in the releasing of water through evaporation and the absorption of Carbon. No fracking or destructive mining processes are employed, and no synthetic, unsustainable, or toxic additives are used. It’s just rock, turned into a plaster, and then back to rock again.

In fact, the amount of Carbon absorbed by the curing process offsets any carbon emission from its production, resulting in a carbon neutral surface that contributes to green building certifications such as the Leed program. No volatile organic compounds (VOCs) or toxic off-gassing, but rather a surface that contributes to the improvement of the environment and brings the luxury of natural stone into your home or business. When you open the bucket, it literally smells like rocks ;)

Natural lime-based plasters are 100% recyclable and reusable, leaving no toxic or synthetic trace if ever removed. The product, if ever removed, can be recycled, used to manufacture other building materials and products.

No VOCs, Toxins, or Fumes

Those ancient innovators couldn’t have known it, but what they discovered would one day serve an important function in our Carbon-heavy world - creating surfaces that filter carbon out of the air to reduce the impact of climate change.

Another highly important feature of Venetian Plaster (I’ll just call it that, it’s simpler) is its resistance to mold, bacteria and other microbes. The pH of the lime plaster itself is very high (alkaline), the same level on the pH scale as soaps and bleach. This is not a habitable environment for the growth of living things (mold, mildew, bacteria, etc.) and reduces the amount of surfaces in your home or business that you need to worry about when it comes to health dangers lurking around. Again, while they couldn’t have known it, their ancient discoveries have become incredibly relevant in an age of virus and pandemic.

Naturally Anti-Fungal & Anti-Bacterial

This might seem obvious, but natural lime-based plasters are also fireproof. It turns back into rock. Doesn’t burn. This means it also doesn’t contribute to the available fuel - and thus, heat - in the event of a fire, serving as a fire-break to slow the spread of the flames, and provide additional precious time to get out.

Rocks don’t burn.